Typescript

Typescript is the best gift you can give your future-self. Hyperion brings the gift of types to every corner of IIIF.

This page will introduce an unofficial member of the Hyperion framework, used internally by all of the other libraries and tools, and something that you can use without using anything else in the framework (if you want!).

Definitely IIIF

One of the core parts of Hyperion and all of the libraries that make it up are the Typescript types. These are used to both improve the experience of developers using the libraries and also to ensure IIIF-related bugs are kept to a minimum. Every part of the IIIF specification has been hand-typed (twice!).

The first set of types are a to-the-specification implementation. That is, the required fields are required types and the optional fields are optional types. Whenever you request IIIF JSON from an unknown source, you can cast its type to, for example, a Manifest. This will ensure that when you are requesting fields from the manifest, you are doing so safely and not going to run into cannot read BLAH of undefined.

A nice side-effect of writing all of these types, is that it can also be used as a complete IIIF validator.

To get started using the types, you will want to install the NPM package. Throughout this site, the examples will use Yarn package manager but the same will work with NPM.

$ yarn add @hyperion-framework/typesUsing with Typescript

To get the most out of the types, you will want to use Typescript. This will allow you to create functions and classes that are correctly typed with IIIF resources, passing around these objects safely.

The most common use case will be fetching a manifest, and then casting it's type.

import { Manifest } from '@hyperion-framework/types'

async function myManifestFetcher(url: string): Promise<Manifest> {

const req = await fetch(url);

// Return the JSON and cast it to our manifest.

return await req.json() as Manifest;

}Now you are going to want to ensure that this is actually a manifest returned in the JSON, using the type field and context to ensure that it is a Presentation 3 resource. Elsewhere in your code you will see other types being used from your manifest.

// lets fetch using our method we just created

const manifest = await myManifestFetcher('https://.../');

// typescript knows this is a Canvas, and this is an ID

const id = manifest.items[0].id;

// it knows that this is an object, with string keys and array of strings as a value

const label = manifest.items[0].label;

// this works for all properties

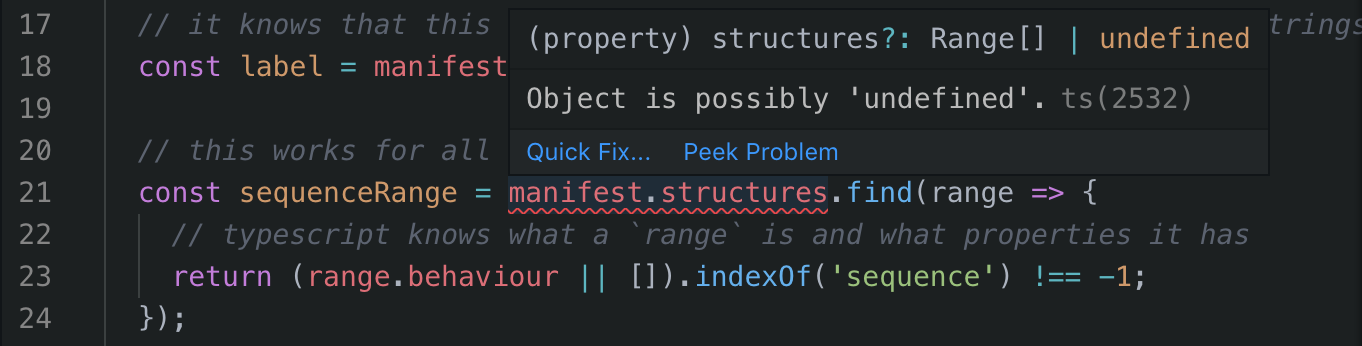

const sequenceRange = manifest.structures.find(range => {

// typescript knows what a `range` is and what properties it has

return (range.behavior || []).indexOf('sequence') !== -1;

});You can see that I'm making some assumtions with these examples. I'm assuming that every manifest will have at least on canvas, and that canvas will always have a label (as per the specification). I'm also assuming that the manifest will have ranges (under .structures) which may not always be the case. If you have your Typescript set up with a strict configuration, this will throw up an error.

Click on the image below to see this error live in the CodeSandbox online editor

This really highlights why we use normalization. You can read a quick summary below, or view the complete section for more detail on the benefits of it.

Using with JavaScript

All Hyperion projects use these types internally, so if you're using an editor like VSCode or Webstorm you can get the benefits of these types just by using the libraries! Check out the Vault for examples and Code sanboxes to experiment the javascript support.

Definitely Annotations

Similar to IIIF resources, the annotation specification is also written in Typescript. There are two flavours of the annotation Types, one for pure W3C annotations, covering every valid annotation and a second covering the IIIF extensions to annotations, supporting a wider range of annotation types and extra fields that the IIIF specification allow on annotations, such as service properties on images.

Now, although the annotation specification is typed, it is still extremely difficult to work with. A normalization step does happen when importing annotations, but it there is only so much that this can do. There is a work-in-progress library (Pattern matching) that aims to make this easier to parse and display annotations.

Sort of probably Annotations

The main issue with annotations are their flexibility. Annotations are made up from many possible fields, with the 2 main fields being body and target. Let's take a look through all of the possible ways to describe a target, as a way to demonstrate the problems with working with every possible annotation.

Here's a trimmed down top level annotation, you can see right off of the mark that target can either be a single target or an array of targets. This is fairly easy to work around though, simply forcing an array of values seems to work well.

type Annotation = { target?: AnnotationTarget | AnnotationTarget[]; }Let's now set into AnnotationTarget and see what it's definition is.

type AnnotationTarget = W3CAnnotationTarget | ContentResource;

type W3CAnnotationTarget =

| Target

| ChoiceTarget

| TargetComposite

| TargetList

| TargetIndependents;We will ignore "content resource" for now, as that is its own rabbit hole! But you can see that the valid W3C annotation targets are:

- Target - a single resource, either external link or embedded JSON

- ChoiceTarget - a choice of Targets, where there can be multiple targets to choose from

- TargetComposite - similar to choice where there are multiple targets, but they all apply together. This could be a box highlighting some words on a book, where the highlighted region spans multiple lines (so multiple boxes)

- TargetList - again, simliar to choice, but this time the annotation applies to each of the items, while maintining the order. For example a list of bookmarks could be stored in this way.

- TargetIndependents - again, simliar to choice but the intention with this is that they don't represent the same thing, instead the body of the annotation or motivation applies equally to all of the items in the list.

So thats the next level of targets. Effectively adding either a single target, or multiple target but with specific meaning behind them, which all could affect the user interface driving them. Next let's look at what a Target is made up of (finally!).

type Target = string | ExternalWebResource | SpecificResource;

type ExternalWebResource = ResourceBaseProperties & {

id?: string;

type: 'Dataset' | 'Image' | 'Video' | 'Sound' | 'Text';

format?: string;

language?: string | string[];

processingLanguage?: string;

textDirection?: 'ltr' | 'rtl' | 'auto';

};

type SpecificResource = ResourceBaseProperties & {

id?: string;

type?: 'SpecificResource' | string;

state?: State | State[];

purpose?: AnyMotivation | AnyMotivation[];

source?: LinkedResource;

selector?: Selector | Selector[];

styleClass?: string;

renderedVia?: Agent | Agent[];

scope?: LinkedResource;

};

type ResourceBaseProperties = {

// Lifecycle properties.

created?: string;

generated?: string;

modified?: string;

creator?: Creator;

generator?: Creator;

// Intended audience

audience?: Audience | Audience[];

accessibility?: string | string[];

motivation?: AnyMotivation | AnyMotivation[];

// Rights

rights?: string | string[];

// Other identities

canonical?: string;

via?: string | string[];

role?: string;

};

That's a lot to digest, so let's break it down a little.

- A target can be a string - this usually implies a URL to an external resource, which might itself be a JSON document like these, or a direct link to the resource (such as an image).

- A target can also be an External resource, which is to say a description of a resource that exists at an external URL. The descriptive data should be enough to display it. In IIIF, this is extended to allow for images to have heights and widths, in addition to the properties you see above (defined in the

ContentResourcewe ignored earlier!) - Finally a target can be a

SpecificResourcewhich is similar to an external resource, but is usually only a piece of that resource. For example a section of an Image.

You can see here that there is a lot of types still not shown, and a lot of polymorphic types. Let's take a look at one more interesting example, relating to the specific resource. The selectors.

type Selector =

| string

| FragmentSelector

| CssSelector

| XPathSelector

| TextQuoteSelector

| TextPositionSelector

| DataPositionSelector

| SvgSelector

| RangeSelector<FragmentSelector>

| RangeSelector<CssSelector>

| RangeSelector<XPathSelector>

| RangeSelector<TextQuoteSelector>

| RangeSelector<TextPositionSelector>

| RangeSelector<DataPositionSelector>

| RangeSelector<SvgSelector>;

type RangeSelector<T> = {

type: 'RangeSelector';

startSelector: T;

endSelector: T;

};That's quite a list! Each of these selectors also has a property called refinedBy which itself is another selector to further select a selection. So I think that summarises the challenges with annotations and the model they sit upon. Type-safe access to annotations is one thing, but it doesn't change the fact that annotations can be structured in millions of different ways.

Normalized variations

The second set of types are for a normalzed version of each type of IIIF resource. Normalization is covered in an uncoming chapter, but the summary of how a normalized resource differs from a normal one is in three ways:

- Every field exists, even if its empty (null values and empty arrays added)

- Embedded items are extracted and replaced with

{ id: '..', type: 'Canvas' }for each type. - Default values that are implied are implemented (viewing direction for example)

This makes it much safer for grabbing fields from unknown IIIF resources, as you can guarentee that the fields you are requesting will at least exist.

Let's compare the base properties of an annotation thats not normalized and one that is.

Normal annotation

export declare type OtherProperties = {

// Lifecycle properties.

created?: string;

generated?: string;

modified?: string;

creator?: Creator;

generator?: Creator;

// Intended audience

audience?: Audience | Audience[];

accessibility?: string | string[];

motivation?: AnyMotivation | AnyMotivation[];

// Rights

rights?: string | string[];

// Other identities

canonical?: string;

via?: string | string[];

};Normalized annotation

export declare type OtherPropertiesNormalized = {

// Lifecycle properties.

created: string | null;

generated: string | null;

modified: string | null;

creator: CreatorNormalized;

generator: CreatorNormalized;

// Intended audience

audience: Audience[];

accessibility: string[];

motivation: AnyMotivation[];

// Rights

rights: string[];

// Other identities

canonical: string | null;

via: string[];

};Immediately you can see that the normalized variation has much more certainty with the properties. There no missing properties so you can do annotation.generated without having to check if that property exists first. Secondly, anywhere that could have an array has turned into an array, allowing you to do something like annotation.creator.map( ... ) safely.

This normalization step is still in early days, and improvements will be made to normalize all the way down the chain to annotation bodies and targets to make them much easier to work with. Hopefully this will in turn allow UIs to be built that can take full advantage of the scope of annotations and also encourage more exotic annotation formats to really push what you can do with them.

IIIF resources are also normalized, which will be covered more in the main Normalization section.